Is it harder, to give up a genetics, as a traditional surrogate?

If you know me well , you’ll know that I often get on my high horse when I hear misinformation spread about IVF, donor conception or surrogacy. Traditional surrogacy is a favourite topic – I often hear that it’s illegal, despite it being legal across Australia. Why do people think it’s illegal? I think it’s because many people cannot fathom a woman willingly giving away a child where she is the genetic mother. Surrogacy is easier to understand perhaps, if we believe the surrogate is not giving away her genetic child.

I’ve also heard that traditional surrogates will not relinquish the child to the intended parents. I’ve heard lawyers, clinic staff and counsellors make this declaration. I had one clinician tell me “we don’t do traditional surrogacy, because she probably won’t hand over the baby” – despite that I had just given birth, as a traditional surrogate, and had willingly done just that. Other traditional surrogacy teams have been denied access to treatment, not because of any legal restrictions, but because of the clinic’s own pre-conceived ideas about the surrogate not handing over the baby.

So, what does the law actually say?

Traditional surrogacy is legal in all states and territories in Australia. Victorian legislation provides that an ART provider (IVF clinic) cannot assist with a surrogacy arrangement unless approval has been sought from the Patient Review Panel – and the criteria for PRP approval includes that the surrogate is not providing her own oocyte (egg) for the surrogacy arrangement. This leaves most traditional surrogacy arrangements in Victoria to conceive without the assistance of an ART provider – via home insemination.

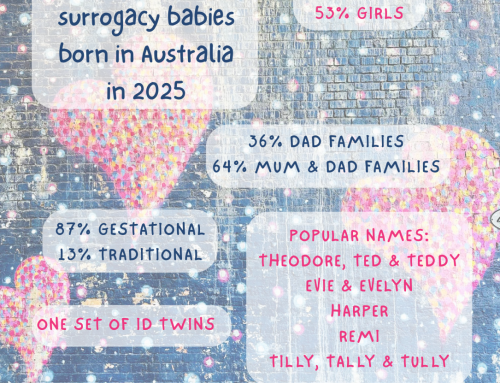

How common is traditional surrogacy?

About 15% of surrogacy arrangements in Australia involve traditional surrogacy – and given there are about 120 surrogacy births in Australia each year, that means about 15-20 involve traditional surrogacy.

Is it harder to give up genetics?

I went on a fact-finding mission, to try and dispel the myths around traditional surrogacy and the belief that she won’t relinquish the child. What I found was most the of myths are exactly that – unfounded and based on pre-conceived and poorly considered ideas, and not on fact. One study I read, Surrogacy: is it harder to relinquish genes? by QUT academic Pip Trowse and published in the Journal of Law and Medicine in 2011, provides less than ten case studies across the UK and Australia over three decades where traditional surrogates have apparently refused to relinquish the child. The commonality in these cases were not of refusals to relinquish, but of a refusal to consent to the adoption court orders. In the majority of cases cited, the child had been relinquished to the intended parents but conflict had arisen between them and the surrogate. My conclusion (which differed from that of Ms Trowse) was that the problem was not the genetic connection between the surrogate and the child, but the poor relationships between the adults involved.

Things that might go wrong in a traditional surrogacy arrangement that are unlikely to go wrong in a gestational surrogacy arrangement, are where the parties have not completed any pre-conception counselling or legal advice. These cases, including cases I have dealt with, involve parties conceiving a child at home, without engaging with any counsellor or lawyer, and by the time the baby arrives the cracks have begun to show in the relationship. Unless the legal and counselling steps are followed, these arrangement are not surrogacy and really should not be considered in the same category as surrogacy arrangements that have followed the legal process.

Is it harder, emotionally, to relinquish a child, as a traditional surrogate?

There aren’t many traditional surrogates, many less than gestational surrogates. And most surrogates have only experienced either being a traditional, or a gestational surrogate, so it is difficult to say whether relinquishing as a traditional surrogate is any harder than as a gestational surrogate. But I also know many traditional surrogates, ten that I can think of off the top of my head, that have birthed in the last two years, and none of them have had difficulty relinquishing the child. All the traditional surrogates I have spent time with are happy, satisfied with their experience and comfortable with having relinquished the child. Any of us who have faced challenges in our journeys do not ascribe it to the genetic relationship with the child.

Recent studies conducted by surrogacy counsellor Narelle Dickinson and Lotus Health in Queensland found there to be no significant difference between the experiences of traditional and gestational surrogates.

What conclusions can we draw from all of this?

I’ll be the first to admit that all surrogacy is complex, and I think traditional surrogacy has the potential to add layers of complexity on top. Surrogacy is anything but simple. All parties entering a surrogacy arrangement – gestational or traditional – should access good support from a surrogacy counsellor and make sure they follow the necessary processes so that they can obtain a Parentage Order. All decisions should be made with the child’s best interests at heart – and for traditional surrogacy, this should be with consideration of what relationship the child (and other children) might want with the surrogate in the future. Known donor conception is in the child’s best interests, and this extends to traditional surrogacy for the same reasons.

If you are considering traditional surrogacy as an option, have no fear that the surrogate won’t hand over the baby. Make sure you follow the processes and access advice. Make decisions in the child’s interests. But don’t be turned off by misinformation and myth.

You can find more information in the free Surrogacy Handbook, reading articles in the Blog, by listening to more episodes of the Podcast. You can also book in for a consult with me below.