I recently spoke at the Melbourne Law School’s Health Law and Ethics Network, on the subject of surrogacy and ethics. Below is my speech.

Thank you for having me and giving me the opportunity to speak about my experiences as a surrogate, and my thoughts on the ethics of surrogacy and motherhood.

By way of background, I wanted to share my own surrogacy story and story of motherhood – of infertility, egg donation and surrogacy. Many years ago, my husband and I decided to have children, but after several years of trying, we turned to IVF. We went through an IVF cycle, produced 18 eggs, 15 embryos, and had a total of seven transfers before falling pregnant with our first son, who is now 9. Two years later we decided to try for another child, and whilst saving for another round of IVF, we fell pregnant with our second son, who is now 6. We decided then that our family was complete, and I decided that I wanted to help someone else have a baby, so I became an egg donor.

I felt some tension that I was very much finished my own family but had some grief about the fact that I wouldn’t ever be pregnant or experience childbirth again. Eventually, that tension led me to the idea of surrogacy, and my husband and I talked about it extensively before meeting the couple that would become our intended parents. We met them in 2016 and completed the surrogacy process with legal advice and counselling, psychological assessments, blood tests, police checks and child welfare checks. We gained approval from the Victorian Patient Review Panel for our arrangement. I was eventually able to fall pregnant, with my own egg, and gave birth to their daughter, in January 2018.

I tell the story of my journey to motherhood, and as an egg donor and a surrogate, to give some context to the discussion we’re having today. I also want to talk about our ideas of motherhood and what it is to be a mother. I am a mother to my two sons, and whilst the journey to my first son’s conception was challenging, my desire to have a child was never challenged. The IVF process necessitated blood tests, counselling and police checks. Our second son’s conception didn’t involve any scrutiny or intervention whatsoever, and really if anything it was expected by the community around me that I would have at least two children. No one ever sat me down and asked me if I really understood the risks I was taking – to my physical or emotional well-being, or to my lifestyle. Did I really appreciate that parenting is permanent, that it’s relentless and unforgiving and that there’s no undoing it once you’ve brought a child into the world. I am forever their mother, in sickness and in health, in good times and bad. If you are fertile and able to conceive with your partner then having a baby or two is not only acceptable but expected.

I think it’s interesting that we view the decision to procreate between two fertile opposite-sex people through a different lense to how we view the decision to procreate between consenting adults, when the intention is for someone else to raise the baby. I am curious that the decision to have two children and raise them with my partner was subject to much less scrutiny than my decision to have a baby and give her to someone else to raise. And yet, my experience of motherhood is that keeping and raising the children is much more challenging than giving a baby to someone else and watching them raise her.

That is not to say that I think surrogacy should not be regulated or that anyone wanting to enter into a surrogacy arrangement are entitled to do so. However, I do feel quite strongly that when we provide robust, healthy regulation of surrogacy, we must accept that it is a legitimate way to grow a family and it is a legitimate choice for a woman to carry a baby as a surrogate. If we accept that a woman has the bodily autonomy to decide if and when to have children, we must accept that she has the bodily autonomy to decide to have children and not raise them.

There are three concepts that I’m going to explore.

Firstly, that we expect that a woman has a right to bodily autonomy, and this extends to her right to choose how many children she has and when;

Secondly, that the rights of the child are paramount; and

Finally, that there is no entitlement to a child, but that the desire for a child is understandable, and might be considered natural.

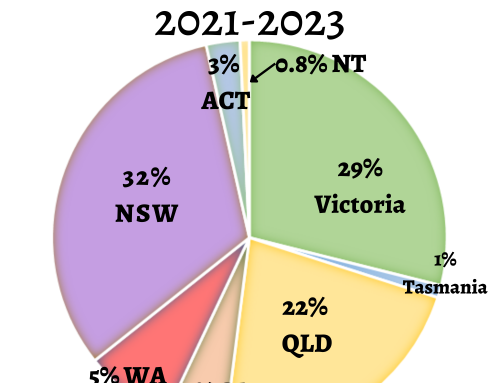

Surrogacy can be potentially exploitative, and risky, for the women and children involved. I completely agree that it can be both those things. I think there’s a dichotomy whereby surrogacy must be considered either rainbows and sunshine, or exploitative, risky and terrible. I think there’s a lot of room in the middle, to talk about surrogacy being something that is both risky and really amazing, and that the answer is to ensure there is proper regulation to protect the rights of the child and the bodily autonomy of women. I also believe there is an opportunity to build a best-practice model of surrogacy, which ensures the best interests of the child remain paramount and the surrogates’ bodily autonomy is protected, and that this is achieved through regulation, education, appropriate support and counselling with qualified professionals, a robust legal process and encouraging Australians to pursue surrogacy within our own borders, where we can regulate and support the participants appropriately.

I’m focusing on the first concept, that women have bodily autonomy and can express that as surrogates. I will touch on the other two concepts, and they are all important and intertwined in a surrogacy arrangement, but my focus today will be on the fact that a woman’s right to choose to be a surrogate is inalienable from her right to express bodily autonomy and is an expression of motherhood in itself.

Australian surrogacy laws ensure that women who are surrogates retain their bodily autonomy, even whilst carrying a baby for someone else and even though they may not be genetically related to the baby. Surrogacy arrangements are not enforceable, because to make them enforceable would be to place the interests of the intended parents above that of the child and the pregnant woman.

When we talk about the risks of surrogacy, including the risks of pregnancy and birth, there’s an assumption that surrogates have not considered these risks and are not making informed decisions. There’s some paternalism involved surely, when we claim that the risks of surrogacy are too high and that the choice to be a surrogate should be taken away from the woman. Heterosexual fertile couples take the same risks when they conceive a child, yet they generally do not consider the endless list of possible consequences to themselves, their families, or their relationships. And if they do, no one scrutinises or criticises their decision. Whilst we expect surrogacy arrangements to undergo rigorous scrutiny, including counselling, psychological assessments, police checks, legal advice, child welfare checks, etc, we don’t expect the same of anyone else when making the choice to have a child. There are good reasons for these checks and balances, but we cannot say that a woman offering to be a surrogate has not considered the risks before she makes the decision to go ahead. If we claim that a woman wanting to carry a baby for someone else should be prohibited because of the risks to her body and well-being, then surely we have to acknowledge that those risks apply to every woman who has a baby and raises it herself.

Surrogates are generally risk-averse, knowing the risks of pregnancy and childbirth, and don’t want to place their own children at risk of losing a mother or undermining their existing relationships. There are always serious discussions about life insurance and health checks before proceeding with the surrogacy, and about the potential risks to ourselves and our relationships. We know the risks, and in fact if we hadn’t considered them, there are plenty of people who will enlighten us. That said, all the surrogates I’ve spoken to agree that if we had known that some of those risks would come to fruition, we would still pursue surrogacy. “What’s the point of life if you’re not living it?” they say. I know of surrogates who have experienced post-partum haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia, emergency caesareans, hysterectomies, vaginal prolapse, uterine infections, not to mention breakdowns in their marriages and other relationships, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. And yet, if asked if they would have still carried for someone else in hindsight, the majority of them answer in the affirmative. Many of them not only answer in the affirmative, but are planning on doing it again. And yet, women planning to have their own baby are not given this shopping list of risks and consequences and asked to reconsider their family plans.

When we limit a woman’s right to choose to be a surrogate, we are assuming that she lacks the capacity or intelligence to make the decision for herself. A choice to be a surrogate must be offered freely and without coercion. If we argue that the risks of surrogacy are too high, we are removing the decision-making power from the woman and assuming that she doesn’t know what is best for herself or her family. And yet, the women who are surrogates are better informed of the risks and consequences than anyone else.

Critics of surrogacy claim that it is exploitative of women and their bodies. Australian, altruistic surrogates feel that the decision to use their body to help someone else, is entirely empowering. I have never felt more powerful and untouchable than when I gave birth to a baby for someone who couldn’t do it themselves. I can do what men cannot do and I have the power to decide to do it. Surrogates hold the power in altruistic arrangements precisely because we can do something the intended parents cannot. Surrogates want to make the world a better place, and we make the decision to exploit our own bodies to help someone else, precisely because we have the agency to do so. A woman’s bodily autonomy must extend to the right to use her body for surrogacy if she chooses.

In any event, the argument that women are being exploited really supports the need for regulation, not abolition. We want women to be empowered, able to exercise agency, not be enticed by financial reward, and to do that we need robust regulation of surrogacy. Surrogates in Australia are generally financially stable, educated and have their own careers. We do not fit a stereotype of a poor, helpless, exploited uneducated woman forced into surrogacy to support her family. It is precisely because of the risks associated with altruistic surrogacy that women who become surrogates are not in poverty or doing it to make money. We can believe that all sorts of activities are risky, including sky diving and mining, but that doesn’t change our belief that people have the right to partake in them with proper regulation.

I want to explore this idea that the best place for a child to be is with the birth mother. Critics of surrogacy argue that a child has a right to remain with its birth parents, and that a surrogacy breaks a primal bond between the birth mother and the baby, to both their detriment. These same critics believe a woman should have the right to conceive a child which she intends to raise herself. The choice to grow your own family is not questioned. The problem, it seems, is the idea that a woman might want to conceive, carry and birth a child, but not raise it herself. So then, one has to wonder whether the problem is that pregnancy and birth is too risky, or is the problem that the baby won’t remain with the birth mother? Critics accept that we can have children if and when we choose, but only if we are determined to raise them ourselves. The conceiving and carrying is ok, but we expect that women will raise the babies they birth. The practice of surrogacy is quite old in some cultures, including the practice of Whangai in Maori culture, whereby a child is birthed by one woman and raised by others in the community as determined by what is best for the family and community as a whole.

The traditional version of family in our western culture is that women must carry and birth children and then raise them with absolute devotion and tenderness. And yet, so many families do not fall into that stereotype and we know that families, women and mothers come in many different forms.

So let’s explore this idea of motherhood further. I am mother to my two sons; their Mum. I conceived and birthed them with the intention of raising them with my partner, their father. I am birth mother to the baby I conceived as a surrogate. I conceived and birthed her with the intention that she would be raised by her Dads. My expression of bodily autonomy, of motherhood, is as her birth mother. I expressed my reproductive autonomy, of being able to conceive and carry her, and I expressed myself as a fertile woman, to be her birth mother. But I never wanted to raise her. That is the version of motherhood I did not plan for. I never intended on mothering her. When critics of surrogacy claim that the rightful place for a child is with the birth mother, it is to deny that motherhood and mothering comes in many forms, and that the best place for a child is not necessarily with the person who birthed them or with those that they share a genetic connection with. A woman is capable of more than just motherhood in the traditional sense of birthing and raising children. When critics claim that all surrogacy is exploitative, what they are really saying is that there is only one, correct way to be a mother, and that is to keep the baby and raise it ourselves. I find that particularly reductive and patronising.

We know that genetics alone do not make a parent. I think about the sense of obligation and ownership that exists in many parent-child relationships, and how they are often not in a child’s best interests. I have never seen my children as possessions. I think of how being fertile and heterosexual are not qualifiers for being good parents, and that we know that children raised in other families are healthy and well-adjusted regardless of their genetics and family creation. I am a birth mother, and by far the best thing I ever did, and did for her, was to hand her to her fathers so that they could be her parents. My act of selfless, unconditional mothering for her was not to raise her but to give her to her Dads.

I want to be clear that I agree with regulating surrogacy so that women agreeing to be surrogates still pass health checks, and they and their partners undergo psychological assessments, counselling and the legal process. I also believe the intended parents should undergo the same assessments and screening.

We know that a child has a right to know their identity, and that includes the right to information about their donor heritage and birth story. We know from donor-conceived people that knowledge and information can be crucial in their development and forming their own identity. We should be working towards building positive surrogacy stories that ensure the child’s interests are front and centre in everyone’s minds. Surrogacy is hard work, the relationships are complex, and we enter unchartered territory when one person gives a baby to another. Children born through surrogacy are loved by many and surrounded by a village. They know they were wanted and created with love. We are building new neural pathways and establishing relationships and family outside the traditional construct. But the rewards are immense and as we push ourselves to the limits of human experience, we should be supported to do so.

Fundamentally, a woman must have the right to choose what she does with her body, the number of children she has and when, and whether she raises the children she births or gives the opportunity of parenthood to others. To quote Premier Daniel Andrews this week, ‘What you do with your body will always be your decision.’ Even if we do not agree with a woman’s choice to be a surrogate, we must accept that she has the autonomy to make that decision for herself and we must provide a framework and appropriate regulation to protect her interests and that of any children born through the arrangement.

So, then returning to the three concepts I raised earlier:

- Women must have bodily autonomy and be able to determine the number of children they have and when;

- The rights of children are paramount; and

- Intended parents have a desire to have children, even if there is no right or entitlement to have a child.

My conclusion then, is that as long as a woman wishes to carry a baby for someone else and the intended parents desire a child, then proper regulation is required to facilitate that to occur to ensure that the child’s rights remain paramount. We cannot demonise intended parents for desiring children, and we cannot demonise women who wish to exercise their bodily autonomy by having children, but we can provide a safe and regulated environment to protect children and the well-being and bodily autonomy of women. That includes ensuring that children have access to information about their donor and birth heritage and the opportunity for relationships with their birth family. Women who wish to carry a baby for someone else, in spite of the risks, must have their choice respected and protected.

You can read other articles on similar topics – my thoughts on changing Birth Certificates, and other Blog Posts. You can also listen to stories from other surrogates and intended parents on the Surrogacy Podcast.

You can find more information in the free Surrogacy Handbook, reading articles in the Blog, by listening to more episodes of the Surrogacy Podcast. You can also book in for a consult with me below.

Sarah can assist with Surrogacy Parentage Order applications for Victorian surrogacy arrangements. Sarah offers an affordable DIY Parentage Order package to transfer parentage from the birth parents to the intended parents.

Sarah can assist with surrogacy arrangements across all States, including Victoria and cross-border arrangements. You can contact me here. All consults are conducted over Zoom and email. You can book in for a consult with me below, and check out the legal services I provide.