Photo credit: Hermes Rivera

Surrogacy and human trafficking: it happened here.

There was much reporting on the situation in Crete in 2023. I did eight media interviews in five days. My phone ran hot. I’ve had to see my face lit up by bright lights for early morning television.

We should be concerned with the conflicting interests in the surrogacy industry that leads to this situation.

Everyone is understandably worried about the Australian intended parents impacted by the scandal. Parents waiting to meet their babies, or worried about embryos stored at the clinic. And we’re worried about the babies. Their welfare, their parentage and their right to be cared for by their parents.

The question less asked (or not at all) is about the women involved – the surrogates. There are rumours that some have fled Greece and allegations that many of them had been trafficked into Greece for the purpose of egg donation or surrogacy.

Many surrogates were allegedly coerced into donating their eggs or being surrogates. They were underpaid, kept under surveillance, made to undergo medical treatment without informed consent. We haven’t heard much, if anything, about these poor women and their whereabouts or welfare.

This is human trafficking.

This is the legacy of unregulated surrogacy.

And it is reminiscent of what we saw in India, Thailand, Laos and Ukraine. It will be repeated in Mexico and Uganda and Georgia.

Four Corners ran a story in 2019 about the exploitation of women and babies in Ukraine. It is remarkably similar to what we are witnessing in Crete now. Surrogacy in India was likened to ‘baby farms’ in 2008. This story is not new or unique.

If we care about women as much as we care about the babies and intended parents, then we should be outraged about how the surrogates have been treated. About the risks they have been forced to take with their own safety and welfare.

Organisations in Australia run events marketed to intended parents, to send them overseas for surrogacy. This included sending people to the Mediterranean Fertility Institute in Crete. It now includes clinics and agencies in Mexico, Argentina and Uganda. These events are sponsored by Australian IVF clinics and law firms – their representatives speak at the events, alongside representatives from international surrogacy organisations. Services that sponsor events and trade shows should ensure they are putting surrogacy and ethics at the forefront of their decisions.

If you or your organisation sponsor these events or take referral fees or commissions, this is your legacy too.

Anyone involved in referring desperate and vulnerable intended parents to unregulated international surrogacy destinations should be ashamed.

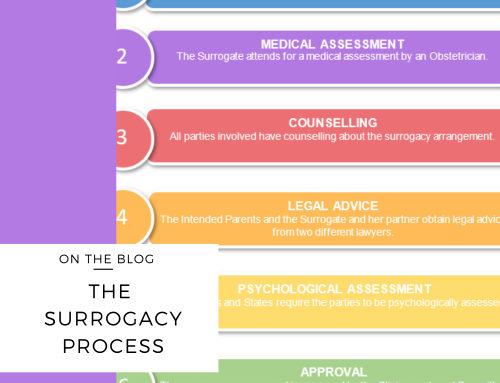

Why are Australian intended parents referred to international surrogacy organisations? Aside from the obvious marketing and messaging to them that international surrogacy is a better option, surrogacy in Australia also has its challenges. There are only less than 150 surrogacy births in Australia each year. Most intended parents find a surrogate within their existing friends and family networks – 79% of my clients have a surrogate already known to them. The remaining 21% are lucky enough to find a surrogate on social media, including the Australian Surrogacy Community on Facebook. There are laws against advertising for a surrogate in several states in Australia.

Secondly, we only allow altruistic, unpaid surrogacy in Australia. Many surrogates, including myself, are not motivated by money and there are concerns about commercial surrogacy undermining the autonomy of the surrogate and the best interests of the child. However, if we are to consider ways of making surrogacy in Australia more viable, we need to have a conversation about compensated surrogacy.

In positive news, the Australian government announced a review of Australia’s surrogacy laws which will happen in 2025 and 2026.

There are ways we can regulate compensated surrogacy, where a surrogate is paid for her time, effort and the risks she takes in pregnancy and birth, without undermining her ability to exercise her autonomy. And we can make sure that payments are not made in exchange for handing over the baby, and to ensure the ongoing protection of the best interests of the child.

The situation in Crete, and in Ukraine, India and Thailand before it, should be the impetus for change for surrogacy in Australia. Unless we overhaul our laws, we will continue to see desperate and vulnerable Australian intended parents enter surrogacy agreements in other countries that place themselves, the surrogates and the babies at risk.

If you are new to surrogacy in Australia, you can read a broad overview for surrogacy in Australia and how it works.

You can find more information in the free Surrogacy Handbook, reading more articles in the Blog, by listening to more episodes of the Surrogacy Podcast. You can also book in for a consult with me below, and check out the legal services I provide.