If I had a magic wand and could change surrogacy law in Australia, what would I do?

One law to rule them all.

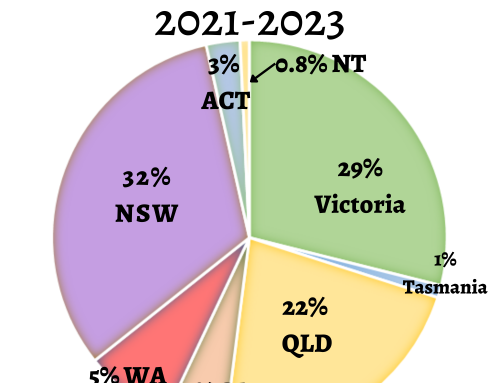

We have eight states and territories, and eight distinct surrogacy law across the country. The inconsistencies and different laws result in inequities in accessing services and treatment, and people engaging in medical tourism as they cross borders to access the surrogacy laws that meet their needs.

Surrogacy in all states involves pre-conception criteria and post-birth processes to recognise the intended parents as the parents of the child born. The processes in each state are different, and there are inequities in the timeframes and cost. For example, the process in Tasmania involves minimal paperwork and a court filing fee of less than $200; the process in New South Wales involves 6-8 Affidavits and a filing fee of about $1,300.

Uniform surrogacy laws across Australia would resolve the inequities and make the processes easier and consistent. There would be no reason to move interstate to access services.

The following criteria already exist across most state surrogacy law, and in my mind, should continue in the future:

- There must be a social or a medical need for surrogacy – but there should be no discrimination based on relationship status or gender or sexuality.

- Intended parents and birth parents should all be over the age of 25.

- All parties must engage with pre-conception surrogacy counselling with a qualified fertility counsellor.

- All parties need to obtain independent legal advice and sign a written surrogacy agreement.

- The surrogacy arrangement must be unenforceable, other than the surrogate’s out of pocket expenses.

- The surrogate’s right to autonomy must be protected.

- The best interests of the child must be paramount.

What would I change?

The most expensive and document-heavy parts of surrogacy usually occur after the birth, with the application for a parentage order. The parentage order is the mechanism to transfer parentage from the birth parents to the intended parents. It always involves a court application, which involves affidavits and reports and lawyers.

But what if we simplified it, and removed the court application process entirely?

Commercial or altruistic surrogacy?

Many intended parents feel compelled to pursue surrogacy overseas, including where commercial surrogacy is legal. It can be difficult to find a surrogate in Australia, and more babies are born overseas each year to Australian intended parents than babies are born here in Australia.

The debate about commercial surrogacy is age-old. There are many arguments for prohibiting commercial surrogacy, including the best interests of the child, protecting the rights of the autonomy of women. But equally there are arguments for paying surrogates for their time, energy and the risks they take. Just as sex work is work, pregnancy and birth are work. There are ways that we can regulate compensated surrogacy in Australia to ensure that surrogates still maintain their bodily autonomy and that the rights of the child can still be protected. If we are serious about supporting surrogacy in Australia, then compensated surrogacy should be on the table.

Decriminalising commercial surrogacy for Australians

Commercial surrogacy is currently illegal across Australia. In New South Wales, Queensland and the ACT, it is also illegal for residents in those places to enter a commercial surrogacy arrangement overseas. The ‘geographical nexus’ provisions mean that intended parents are breaking a law in their home state by engaging in commercial surrogacy overseas. I am not aware of any prosecutions of such cases. The purpose of the geographical nexus provisions appear to be to deter intended parents from engaging in commercial surrogacy, but with 200-300 babies born overseas each year to Aussie intended parents, it doesn’t seem to be serving its purpose.

If we are focused on the best interests of the children born, then criminalising their parents for engaging in something that is legal in the country of destination does not serve that purpose.

An administrative process instead of a court application

If I could change anything, it would be the surrogacy law post-birth process. Instead of a court application, the birth parents and intended parent could complete a birth registration together, to register the child’s birth with the Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, recognising the intended parents as the parents of the child immediately. If there were difficulties, or the birth parents didn’t want to consent, then the parties could still apply to the court to resolve their dispute. In my experience, when there are conflicts or challenges post-birth, it can usually be resolved with the help of a counsellor, and does not result in the birth parents refusing to relinquish the baby to the intended parents.

The idea of an administrative rather than court process is now being considered in New Zealand, where a recent review has recommended a process that does not involve the courts. Surrogacy arrangements in New Zealand currently require the intended parents to adopt their child. The Te Aka Matua o te Ture Law Commission has recommended an overhaul that allows an administrative process so the intended parents can register their child’s birth with the birth parents’ consent, and does away with the post-birth court process.

Consent and the best interests of the child

In most jurisdictions, the birth parents must consent before a parentage order is made unless they cannot be located, or have died. This leaves some arrangements in a tricky situation, whereby the birth parents can withhold consent, to frustrate the intended parents or the process. Should a child’s best interests be determined by whether an adult (who is not caring for the child) consents to the order? This is not the case in other family law cases, where a Judge can make an order that parents don’t agree with.

In Western Australia (where law reform is due in 2023), the current process does not require the consent of the birth parents unless the arrangement involves traditional surrogacy. The intended parents must apply for a parentage order, but it does not require any consent or paperwork from the birth parents. If a parentage order must be made in the best interests of a child, then the consent of any adult should not be required for the order to be made. The best interests of a child can be determined on evidence of who is seeking to care for the child and the circumstances of their care. It should not require the consent of anyone who is not caring, or seeking to care, for the child.

Integrated Birth Certificates

Birth certificates list two parents. For adopted persons, an integrated birth certificate includes information about their parents and siblings at birth, as well as their parents and siblings after adoption. Having an integrated birth certificate is optional, and currently they are available for adopted persons in New South Wales.

If we are focused on the interests of the children born, there should be an option for persons born through donor conception and surrogacy to have a true record of their heritage and birth with an integrated birth certificate.

Commonwealth recognition of children born through overseas surrogacy

The Family Law Act leaves a gaping hole where there should be recognition of intended parents as the parents of children born through surrogacy. Under the Act, birth parents remain the legal parents unless a parentage order is made transferring parentage to the intended parents – and such an order is only available for domestic surrogacy arrangements.

If we are concerned about the best interests of children, then all children need their parentage recognised and they should be treated equally under the law, regardless of their genetic or birth history or where they were born.

So what now?

The Council of Attorneys General (CAG) hold regular meetings to discuss matters of mutual importance across the states. In November 2019, the CAG established Terms of Reference for a Working Group to consider uniform surrogacy regulation across Australia. Since then, and particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been delays and no further progress of the Working Group.

State surrogacy laws have been reformed recently in Victoria and South Australia, with new laws introduced in the Northern Territory in 2022. Western Australia is considering reforms to their surrogacy laws at the time of writing (June 2022). The other state laws were drafted between 2004 and 2012, and arguably should be reviewed. But unless there is enthusiasm from the government, significant change or uniform laws are unlikely to be a high priority.

.

If you are new to surrogacy, you can read about how to find a surrogate, or how to become a surrogate yourself. You can also download the free Surrogacy Handbook which explains the processes and options.

Sarah has published a book, More Than Just a Baby: A Guide to Surrogacy for Intended Parents and Surrogates, the only guide to surrogacy in Australia..

You can find more information in the Blog, by listening to more episodes of the Surrogacy Podcast. You can also book in for a consult with me below, and check out the legal services I provide.