Let’s talk about surrogacy financial compensation. I presented on this topic at the International Surrogacy Forum in Cape Town, in March 2025. think it’s time we talked about paying surrogates for the work of pregnancy and birth. You can read my abridged Surrogacy Financial Compensation Speaking Notes and the presentation slides can be downloaded here.

I think it’s time that Australian surrogates were paid.

I became a surrogate because I enjoyed pregnancy and wanted to offer the opportunity of parenthood to others. I was not motivated by money, but over time I have considered that surrogates can and should be compensated, and that if surrogacy is regulated properly, it can be done ethically. It is possible to be motivated by altruism and empathy for others, and still be compensated for our time.

Do you know who is paid in surrogacy? Everyone else. Fertility clinics, specialists, nurses, counsellors and lawyers. In Australia, the fertility industry is worth over $700 million per year – globally, that figure is more than $US62 billion. We would never suggest that a fertility doctor should work for free, even if they are motivated by empathy and wanting to help people.

Does surrogacy become exploitative when we introduce money? There are valid concerns about exploitation, and human trafficking, particularly in countries where surrogacy is poorly regulated. There are many players in the industry, who exploit surrogates and the intended parents for their own profit. But why must a surrogate not be compensated, when it is the industry around her that is unethical and corrupt?

Criminalising commercial surrogacy on the basis that it is exploitative, assumes that altruistic surrogacy is not exploitative. Yet, everyone in the surrogacy and fertility industry profits from the reproductive labour of women, whether or not surrogates are paid. The one person doing most of the labour, and taking most of the risks, is considered to be exploited – but only if she is paid for her work. Why are surrogates’ bodies subsidising the profits of others, and at their own risk?

If we consider other industries, people are generally paid for their work and are not expected to be ‘altruistic.’ Mining is a risky business. A miner heads down the mines and is paid a salary, as well as hazard pay, to compensate them for the time and risks involved to their bodies and lives. There are about 2.5 deaths for every 100,000 workers in the Australian mining industry every year.

In Australia, there are 8 maternal deaths per 100,000 births. That’s four times the death rate in mining. We pay miners, never considering it ‘exploitative,’ and yet we don’t pay pregnant people. I think most people would consider that sending people down the mines and not paying them, might be considered exploitative, and even akin to slavery.

Altruistic surrogates don’t want to be paid, I hear you say. I understand, and like I said, I also wasn’t motivated by money. But it is possible to be altruistically motivated and still compensated for your time, the work of pregnancy and birth, and the risks we take. We know from studies in the USA that surrogates are motivated by empathy and altruism, even when they are paid. And perhaps, by providing financial compensation for the work of surrogacy, we might encourage more surrogacy to happen within Australia, which in turn may reduce the number of intended parents travelling overseas for surrogacy in unregulated countries.

We should recognise the reproductive autonomy of women to make decisions about their own bodies, including to become surrogates. We can give them the agency to make those decisions, recognise the work involved and pay them for their time and effort. A truly feminist view of surrogacy would see the value in supporting women to become surrogates in regulated frameworks that also promote the best interests of children born.

Australia is reviewing its surrogacy laws! I think it’s time for a major overhaul where we can ambitiously rethink how we support surrogacy in Australia to reduce the need for intended parents to travel overseas.

I was travelling on a Churchill Fellowship in 2025, researching best practice surrogacy to inform law reform in Australia. My journey took me from Melbourne to Cape Town, Ireland and England, Canada and the USA to meet with surrogacy experts, advocates, intended parents and surrogates around the world.

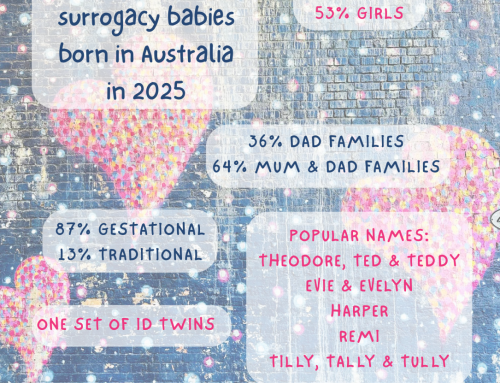

There are only 130-150 surrogacy births in Australia each year, and over 300 babies born via international surrogacy for Australian intended parents. Many children born overseas are born in countries where surrogacy is unregulated, and there are risks for the babies and surrogates, and frequent allegations of human trafficking and exploitation. My Churchill Fellowship seeks to find ways to make surrogacy more accessible within Australia, to reduce the need for intended parents to travel overseas for surrogacy.

If you are new to surrogacy, you can read about how to find a surrogate, or how to become a surrogate in Australia. You can also download the free Surrogacy Handbook which explains the processes and options.

Sarah has published a book, More Than Just a Baby: A Guide to Surrogacy for Intended Parents and Surrogates, the only guide to surrogacy in Australia.

I’ll be back in the office in late May, and my Churchill report will be published later in the latter half of 2025.